There comes a point in your reality when you hope you’re wrong, particularly about people. Especially the ones closest to you. The maternal or fraternal vessels that occupy or share your orbit, if you have a twin like I do. Just like the profound precision in our universe, I too have curated an appreciation for precision. Precision is opportunity. In my line of work, precision is standard. Some (mainly myself) would consider it my source of validation. The logic is simple: if I’m precise, I’m accurate, not necessarily right, especially morally. Being right is vanity; being accurate builds reliability that carries over into every part of your life.

For example, accuracy earns your students' trust, allowing them to confess that they performed poorly because their mom is hooking up with their accountant at 2 AM. Not surprised, Mrs. Shirley always had that strain in her. Not Yesinia Pestis (the pathogen of the Bubonic Plague) the one I teach my students about. But the strain of sloppiness. If you're going to make a mistake, please, be good at it. If you're 56 and work as a paralegal, Contact Trace Theory should follow your regular habits.

Her lack of precision has affected me, too. I don’t like mess, and I especially hate cleaning anything but a Bunsen burner. I don’t agree with being "right," as that opens the door to more philosophical and ethical dilemmas. That’s why I prefer to live accurately. You can count on consistent results, again and again, and tomorrow evening, without the consideration of morality. Accuracy seems to be a recurring theme here. But so is mess.

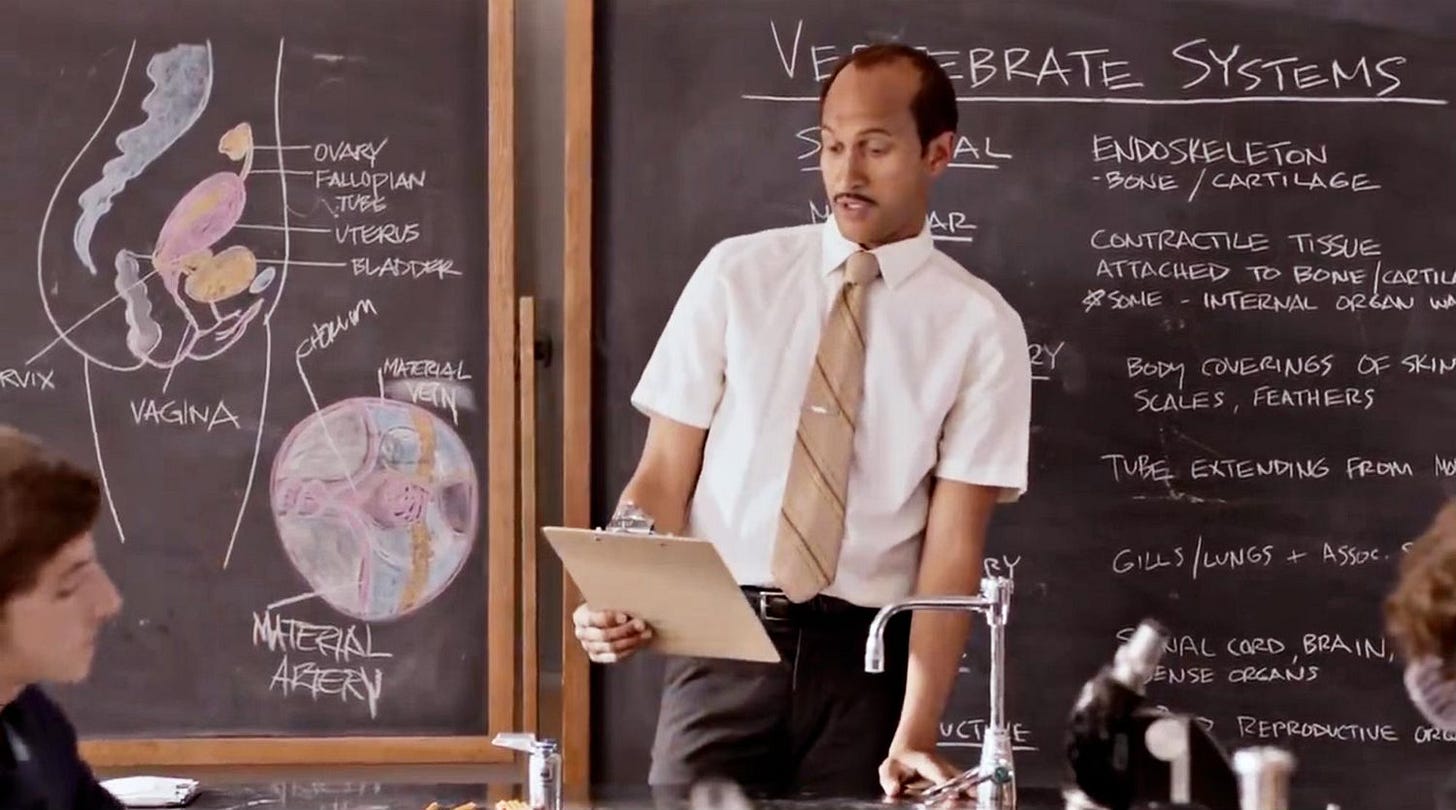

Mrs. Shirley wasn’t with her son’s accountant, she was with my twin brother, Andrew. I can’t face her son tomorrow at 2:30 PM for AP Biology, so I’ll have to teach another lesson instead. A less ethical one, but a more accurate one, at 5:30 PM that same day. To Mrs. Shirley again, for the last time.